Uncategorized

-

The debate over why ecclesiastical institutions took so long to become established in medieval Iceland is not new. Between 1940 and 1970, what became known as the ‘Icelandic School’ framed the issue through a binary lens, portraying a society fractured between a clerical, European sphere on one hand, and an indigenous, national, and secular sphere…

-

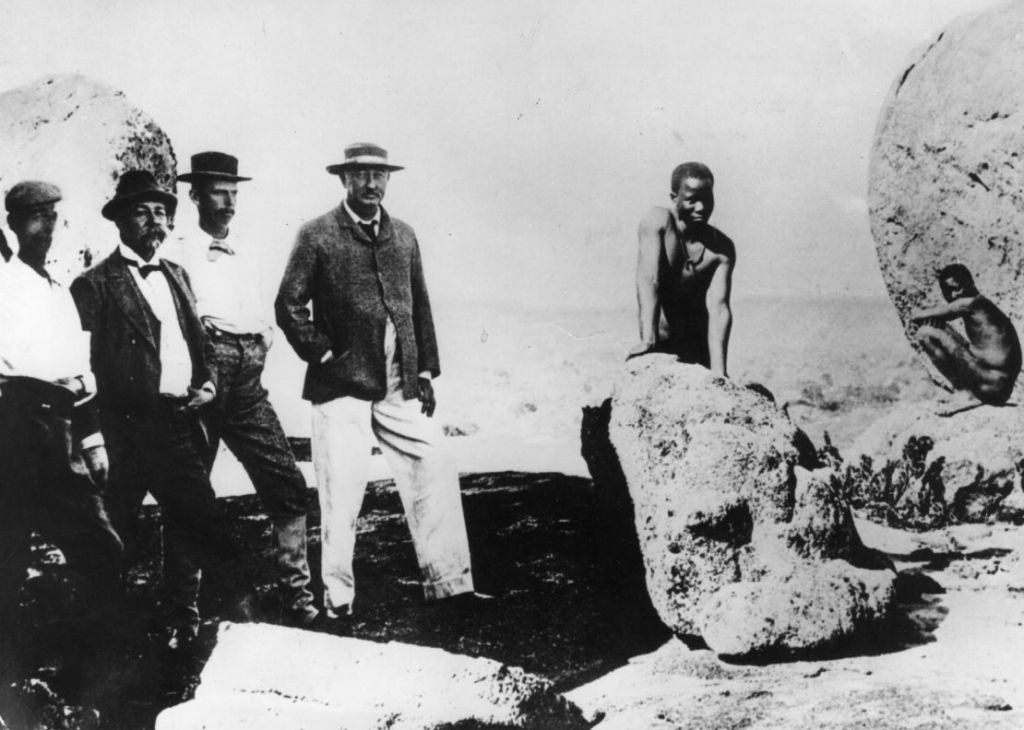

I wrote this essay in 2024 and have been meaning to share it for some time: This essay argues that the colonial economy in Sub-Saharan Africa, following the scramble for Africa, which extended from 1879 to circa 1905, was systematically based upon exploitation that greatly contributed to European development. Firstly, it is important to recognise…

-

Hi All, As I shared in the last post, I have recently been selected through a competitive process to become a member of the UK-China Film Collab with the title Historian & Documentary Producer. Within this role, I completed a film review on a timely film called No Time for Goodbye by Dong Ng. (Please…

-

Some exciting news. In being succesful with my proposal to become a member of the UK-China Film Collab I have been given the title Historian & Documentary Producer. Here I will share my project proposal, however in short I aim to produce a short docu-series entitled Hybridised Plates. The full proposal is below: This proposed…

-

This last week, the Dragon House Chinese Takeaway in York was defaced with racist graffiti. Crude St George’s flags were painted across the shopfront, the word “Chinese” was scratched out, “Cat N Dog” was sprayed onto the window, and on the side of the building, vandals scrawled the words “Go Home.” On a street lined with shops, only the…