I wrote this essay in 2024 and have been meaning to share it for some time:

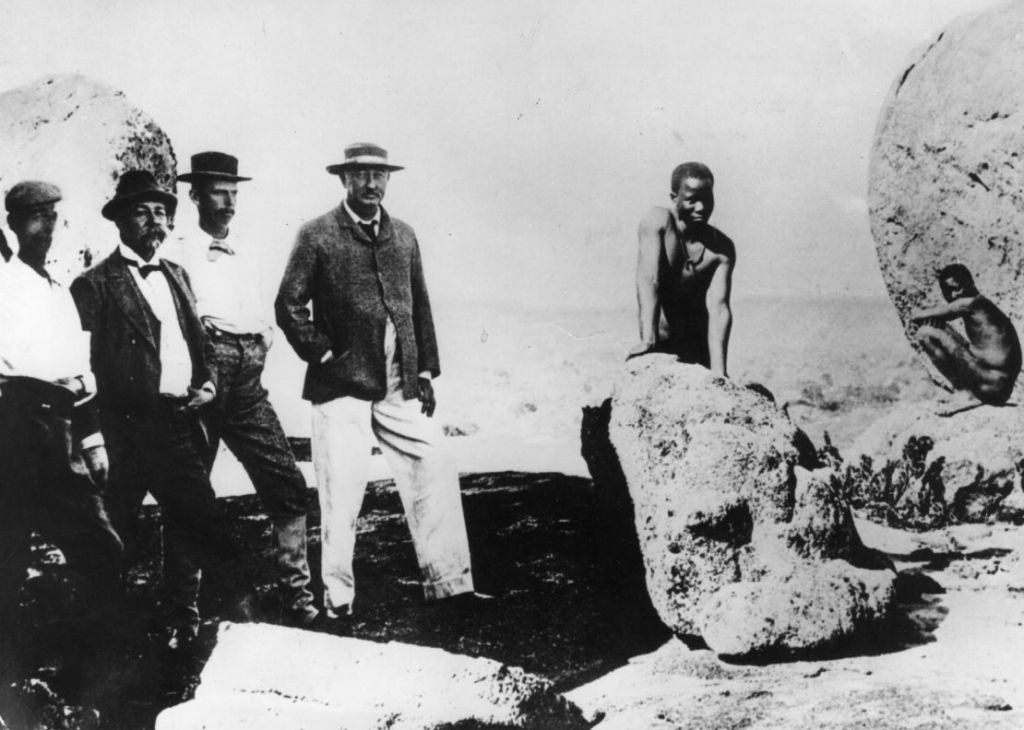

This essay argues that the colonial economy in Sub-Saharan Africa, following the scramble for Africa, which extended from 1879 to circa 1905, was systematically based upon exploitation that greatly contributed to European development. Firstly, it is important to recognise the heterogeneity of the African continent, from geography to the varying forms of colonial oppression, including direct rule, indirect rule, and settler rule. Each variation of colonial rule imposed unique administrative structures and differing levels of racist and exploitative methods, that constitute just a few of the complexities that fall outside this essay’s scope. Despite these complexities, there are significant commonalities across these systems that allow this essay to carry out a broader analysis of colonial economic exploitation. Including the systematic dispossession of land, the imposition of exploitative labour practices, and the restructuring of African economies to serve European industrial needs.

There have been two dominant schools of thought in response to the discussion of colonial exploitation. One side of the argument, in which apologists for colonialism, such as Niall Ferguson, argue that colonial powers brought capital investment to colonies, resulting in improved infrastructure, while suggesting that Africa’s prospects for civilisation and modernisation were improved through the imposition of colonialism. However, this essay subscribes to the adversus of the apologist standpoint, as it fails to acknowledge the human, economic and long-lasting impact of systematic exploitation that distorted African economic structures outweighing any perceived benefits.

In justifying this essay’s position, it is not enough to outlay the motives of European colonial exploitation, as this only serves to focus the puzzle upon the culpability of European Nations. Instead, this essay will demonstrate how colonial powers established and maintained economic exploitation, aiming to recognise the long shadow of colonialism that extends into the present while appreciating Africa’s significant contribution to European economic development.

It is imperative to recognise that it is no coincidence that the scramble for Africa followed the emergence of the European Industrial Revolution. This period of industrialisation marked the end of feudalism in Europe, which had been completely replaced with capitalism, leading to a situation where industrial progress outpaced agricultural progress, and the demands to sustain the European industrial system increased dramatically.

To satisfy such demand, European colonialists aimed to exploit the vast resources of Africa. However, instead of working with African rulers to purchase resources, as they had done when trading enslaved Africans, Europeans moved to portion Africa and her resources up for themselves. Whilst European ships could previously dominate the coastlines of Africa, Europeans could not penetrate the African interior as the balance of force at their disposal was inadequate. This forced collaboration, giving local leaders agency to trade on terms that suited their indigenous economic needs.

Improved military technologies, such as breech-loading rifles and machine guns, which replaced the smooth muzzleloader and flintlock, allowed Europeans to extend upon pre-colonial levels of exploitation. However, a systematic approach to colonial economic control was required to ensure stable resource extraction in supplying the colonial factories. Establishing colonial systems included reorganising the African economy, which included the introduction of cash crops, acquisition of land, enforced labour, and introduction of taxes and colonial currency. These Colonial demands meant more than merely introducing European capitalist systems to facilitate exploitation. Instead, they resulted in the dismantling of the pre-existing vibrant and varied socio-economic structures and systems constructed upon unequalled sub-Saharan principles of communalism, kinship, or extended families.

The coveting of foreign resources did not go unnoticed by influential Nigerian poet and critic Chinweizu, who noted that when Europe pioneered industrial capitalism, her demands on the world increased tremendously and that Europe set out to seize the world’s mineral and agricultural resources. In the tone of Chinweizu, we can establish how colonialists hijacked, seized, and exploited vibrant pre-existing Indigenous economic systems by looking individually at colonial policies of cash crops, land ownership, the introduction of colonial currency and tax systems, and finally, education and administrative systems.

The introduction of cash crops during the colonial period highlights the exploitation and disregard for the sustainable agricultural production of pre-colonial Sub-Saharan Africa. Through production policy, colonial powers prioritised cultivating cash crops such as cocoa in Ghana, coffee in Kenya and Uganda, groundnuts in Senegal, and cotton in Mali, Sudan and Chad, aligning African economies with capitalist global trade demands. In regions like West Africa, smallholder farmers became central to the production of these crops, but colonial policies aimed to limit financial rewards for crop production. Moreover, while cash crop regions occasionally experienced localised economic gains, these gains came at the expense of nearby areas, which were marginalised and underdeveloped as labour and resources were diverted.

The extractive nature of this system ensured that most profits from cash crop production were repatriated to Europe, deepening economic inequalities and leaving lasting economic and cultivation dependencies. These dependencies are starkly highlighted by the contemporary reliance on food imports when, prior to colonialism, Africa was self-sufficient.

Whilst the structures of African political power weakened under colonial rule, colonial control mechanisms over land ownership became increasingly entrenched and exploitative. Pre-colonial systems of land ownership, often rooted in communal access and kinship ties as with the Balanta of Guinea-Bissau, allowed Africans to cultivate and sustain themselves. Colonial administrations, intent on self-interested economic development, upended this balance by reserving vast land areas for Europeans. Africans were not only prohibited from accessing these lands but they were also forced into the wage labour force. The combined exploitation of land rights and land usage resulted in a loss of African peasant autonomy and increasing dependency on colonialist economic systems for survival.

The introduction of cash crops and land ownership policies had created dependency through systematic exploitation; to maximise this exploitation, Europeans needed a large labour force. They deepened the coercion into labour by controlling low wages and introducing colonial-style taxes and currency. Such economic systems aimed to fund the administration costs of the economy, ensuring that Africans paid for the system that oppressed them.

Labour force salaries were paid in the colonial currency, deepening colonial control over financial administration. Importantly, Europeans also ensured taxes could not be paid in kind but only in the colonial currency, forcing Africans to enter the low-paid labour force to earn colonial coin, as a means to pay rising taxes such as hut tax in Rhodesia, or export tariffs on the gold coast. This growing labour force ultimately came at the expense of long-standing African commerce and trade, including, art, mathematics, medicine, and agriculture methods. Where this was already established, it enabled successful resistance to colonial control and economic exploitation, as in the case of Ethiopia. Elsewhere, colonialism coerced workers into dependency on the colonial coin. With low income from primary goods, high cost of increasingly covetable European tertiary goods combined with high levels of tax, family members all had to enter the labour force to ensure a family’s survival. By design, the peasant could not support his family on a single wage, which coerced and created the economic conditions where Africans had to enter the colonial labour force to pay taxes and survive, satisfying the capitalist demand for labour.

Economic exploitation continued post-1945. Even though colonialists in France publicly committed to actively promoting the economies they presided over, the reality of such commitments was less sincere. The French would continue to receive more money from Africa than they spent there. Meanwhile, the British, in the form of government bonds, kept the margin between the low prices paid to African producers and the price the crop received on the world market. Thus, the savings from African farmers were forced into the hands of the struggling post-war British metropolitan economy. When land and labour are combined effectively and create a product that is available in the region of production, this facilitates social advance, the fact that colonialism capitalised upon controlling land and labour to repatriate the profits in their capitalist venture demonstrates European development at Africa’s expense.

It is important to recognise the importance of colonial educational policy in maintaining economic exploitation. Such policy ensured that Africans received only a limited education built to suit the colonial system’s needs. These needs included reading the Bible and taking orders efficiently from Whites. As a result, Africans were, at best, able to function as interpreters, clerks, or messengers in junior roles within the colonial bureaucracy. The administrative system further enfranchised Black African’s into the colonial system of economic exploitation, subsequently creating an artificial class system that had not previously existed in pre-colonial Africa.

This bureaucratic structure was a requirement, in British colonies that operated through indirect rule and required natives to participate in operational bureaucracy. The 1939 figures from British tropical Africa show that 2439 whites ruled in a system over an underestimated figure of 43,114,000 blacks. Such numbers demonstrate that technological advancements in weaponry would not have been enough to maintain exploitation on such a grand scale and that without the compliance of indigenous people, such a system, even for a short period, would have been unsustainable.

In conclusion, to maintain control over production to suit the needs of the ‘Mother country’, an administrative structure was facilitated for colonial powers rather than for the benefit or needs of Africans. Professor Elijah Okon John aptly describes the disarticulation of the indigenous economy, administrative structures and transition to economic dependency, indicating that ‘African Civilisation, Culture, beliefs and values were trodden under feet where colonial powers introduced and imposed religious, political, economic, social, linguistic and administrative systems.’

The colonial economy in Africa exploited the African continent’s resources, labour, and pre-colonial structures for European benefit. This exploitation not only fuelled European industrial and economic development but also left a legacy of underdevelopment, dependency, and inequality in Africa. Understanding the legacy of colonial economic exploitation is crucial for addressing the structural challenges affecting African economies today and recognising the continent’s substantial, albeit unacknowledged, contributions to global progress.

Bibliography

Austin, Gareth. ‘The Economics of Colonialism in Africa’, in The Oxford Handbook of Africa and Economics: Volume 1: Context and Concepts, edited by Célestin Monga, and Justin Yifu Lin, 522-535. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Austin, Reginald Racism and apartheid in southern Africa: Rhodesia; a book of data. Paris: UNESCO Press, 1975.

Chinweizu, The West and the Rest of Us: White Predators, Black Slavers and the African Elite. New York: Random House, 1978.

Colson, Elizabeth. ‘The Impact of the Colonial Period on the Definition of Land Rights,’ in Colonialism in Africa 1870-1960: Volume Three, edited by Victor Turner, 193-215. London: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

Darkoh, Michael, and Mohamed, Ould-Mey. ‘Cash Crops Versus Food Crops in Africa: A Conflict Between Dependency and Autonomy’, Transafrican Journal of History 21, (1992): 36-50.

Ferguson, Niall. Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World, London: Penguin Books, 2004.

Forstater, Mathew, ‘Taxation and Primitive Accumulation: The Case of Colonial Africa,’ Research in Political Economy 22 (2005): 51-64.

Gardner, Leigh. ‘Slavery, Coercion, and Economic Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,’ Business History Review 97, 2 (2023): 199–223.

John, Elijah Okon. ‘Colonialism in Africa and Matters Arising – Modern Interpretations, Implications and the Challenge for Socio-Political and Economic Development in Africa’,

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 4, 18 (2014): 19-30.

Kirk-Greene, A.H.M. ‘The thin white line: the size of the British colonial service in Africa’, African Affairs 79, (1980): 25-44.

Manning, Patrick. Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa 1880-1995, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Nkrumah, Kwame. Africa Must Unite, New York: International Publishers, 1963.

Nkrumah, Kwame. Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, (New York: International Publishers, 1965).

Ocheni, Stephen, Nwankwo, Basil C. ‘Analysis of Colonialism and Its Impact’, Cross-Cultural Communication 8, 3 (2012): 46-54.

Rimmer, Douglas. Staying Poor: Ghana’s Political Economy, 1950-1990. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1992.

Roberts, Richard. ‘Coerced Labor in Twentieth-Century Africa,’ in Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume 4: AD 1804–AD 2016, edited by, David Eltis, et al., 583-609. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, London: Verso, 2018.

Roessler, Phillip, et al., ‘The cash crop Revolution, colonialism and economic reorganisation in Africa,’ World Development 158 (2022): 1-17.

Wu, Yuning ‘Colonial Legacy and Its Impact: Analysing Political Instability and Economic Underdevelopment in Post-Colonial Africa’, SHS Web of Conferences 193, (2024): 1-6.